Printed images in medical books and broadsheets were crucial to how medical knowledge was disseminated in the early modern period, but how were these images made?

Technologies for printing text and images were developed in Europe in the fifteenth century, though they had already been in use in East Asia for hundreds of years. For European cultures, these inventions meant that knowledge—textual and visual—could be produced in multiple almost identical copies much more cheaply, quickly, and reliably than was the case with manuscripts.

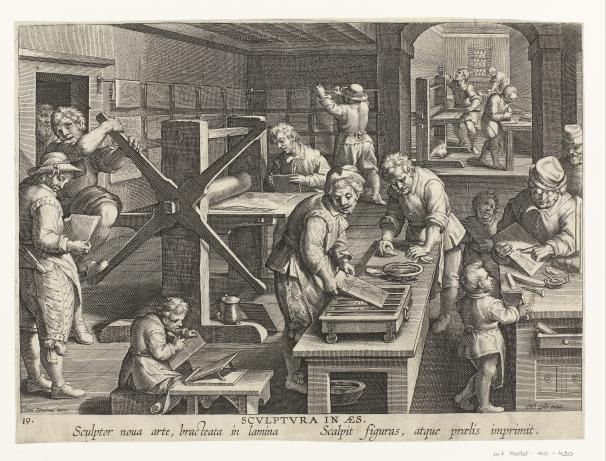

1. Galle, Phillips after Jan van der Straet, Sculptura in Aes, c.1593-98, Engraving. Rijksmuseum.

Printing an image in the early modern period involved carving the design into a block of wood or sheet of metal called a “matrix,” then inking this block and pressing it against paper. This process most often involved a whole host of skilled craftsmen, particularly when the image was intended as a book illustration. The author would often commission the images and direct the artist. The artist would draw the image on paper, and this would sometimes then be passed to another artist who specialized in adapting the image for cutting and transferring to the matrix; the printmaker would then cut the design into the matrix, and then the printer would ink the matrix and print the image.

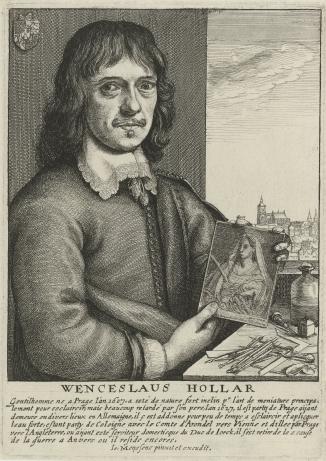

2. Hollar, Wenceslaus, Self-Portrait after Jan Meyssens, c.1649, etching. Rijksmuseum.

This portrait of the famous printmaker shows him holding an etched plate, and sitting at a table covered in printmaking tools.

Many of the most skilled printmakers and artists were initially concentrated in areas of continental Europe such as Germany and Italy, but images were also produced in England through several routes. In some cases, the blocks and plates from which images were printed were loaned or sold abroad for printing English books. In others, English printmakers engraved new blocks and plates by copying continental images. Over time, English-made images became more common and of better quality, as native craftspeople gained skills and knowledge, and as continental printmakers moved to work in England.

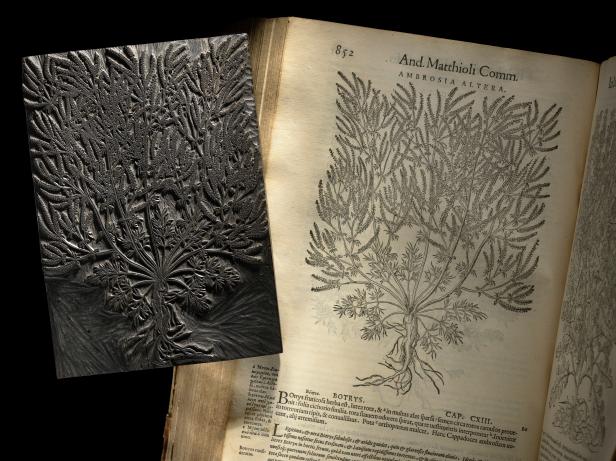

Printed images in early modern Europe came in two types: relief and intaglio. Relief prints were the first and the simplest—they involve carving away the surface of a block of wood everywhere that you don’t want there to be ink. Ink would then be carefully dabbed over the remaining surface and pressed onto paper. Because printing text was also a relief process, movable type and woodblocks could be combined to print a single page with both text and image.

3. Woodblock and woodblock print. Wellcome.

Intaglio prints began to be produced later in the fifteenth century, and grew out of existing practices of engraving decorations onto metal objects such as tableware and armor. Unlike relief printing, intaglio involves carving grooves into a metal plate everywhere you do want there to be ink. Ink is rolled over the plate and then wiped away, so it only remains in the grooves. Paper is then laid on the plate and run through a rolling press, which applies so much pressure that the ink in the grooves is transferred onto the paper. You can often tell an intaglio print by the “platemark”: the line left by the plate’s compression of the paper in the rolling press. Because intaglio prints require a different kind of press to relief prints, it is much less common to see an intaglio print on the same page as printed text. Typically, they were printed on separate sheets and bound into books as “plates.” The major advantages of intaglio prints included the ability to produce much finer lines and more detail, and the ability to layer and crosshatch lines to create tone.

4. Selection of burins and a copper plate for engraving. Wikimedia commons.

There were two main ways of making intaglio plates in this period: engraving and etching. Engraving involves using a very fine chisel-like tool called a “burin” to carve lines into the plate. It was a highly prized skill to be able to control the burin and to produce smooth, even lines. You can tell an engraved line by its smooth, regular shape and the way it tapers at both ends.

Etching involves covering the metal plate in a waxy substance and then using a tool a bit like a blunt needle to scratch the design into the wax. The plate is then submerged in a bath of acid, which dissolves away the metal only where the waxy layer has been scratched away. This technique was easier for artists to learn, because scratching with the needle is a lot more like drawing with a pen than engraving with a burin. You can tell an etched line by its more sketchy, squiggly, dynamic qualities.

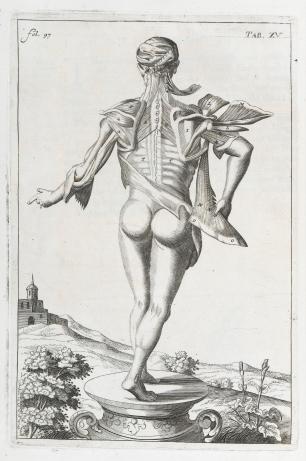

5a. Tab. XV., engraving and etching. From Browne, John, A Compleat Treatise of the Muscles: As they Appear in Humane Body, and Arise in Dissection; with Diverse Anatomical Observations not yet Discover'd ([London]: Tho. Newcombe for the Author, 1681). Wellcome.

Many intaglio prints in this period used a combination of etching and engraving, and it is not always easy to tell the techniques apart, not least because printmakers would sometimes try to make etched lines look like engraved ones! This was largely because engraving was seen as more prestigious than etching. Because of this, most authors called their intaglio prints engravings regardless of whether they were really engravings, etchings, or a mixture of the two.

5b. Detail.

The regular lines of the leg and plinth are engraved, while the sketchier and curvier lines of the foliage are etched.

Different kinds of prints held different places in the early modern world. Woodcuts were the cheapest, most durable, and could be printed alongside text. They were used both for cheap popular books and pamphlets, and for many kinds of technical illustration. Intaglio prints were more expensive and the plates produced fewer copies before wearing out. They were used for more high-status book illustrations and frontispieces. They were prestigious partly because of their capacity to produce finer details and tone, and also through association with the growing trade in “art prints”—printed images that were original compositions by artists, or reproductions of paintings. Engravings in a book usually signaled high quality, and high prices, but in both relief and intaglio prints quality could vary massively. Over the course of the seventeenth century, intaglio prints came to be used more and more as production became cheaper and more streamlined, and as the skills and techniques of intaglio printmaking were expanded and improved. By the eighteenth century, woodcuts had fallen largely out of use except in the cheapest media.

Identifying the kind of print technique used to illustrate a book can, therefore, tell you quite a lot not only about how the book was made, but about the economics of production, the aims of the author, the skills of the artists employed, and the book’s relation to wider visual cultures.

Further Reading

“What is Printing?,” The Met Museum https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/drawings-and-prints/materials-and-techniques/printmaking

“The Making of a Broadside Ballad,” http://press.emcimprint.english.ucsb.edu/the-making-of-a-broadside-ballad/woodcutting

“The Print Workshop in the Fifteenth Century,” Cambridge University Library https://youtu.be/v4ARRcED3Ro

Gascoigne, Bamber, How to Identify Prints: A Complete Guide to Manual and Mechanical Processes from Woodcut to Inkjet (London: Thames & Hudson, 2004 [1986]).

Griffiths, Anthony, The Print Before Photography: An Introduction to European Printmaking 1550–1820 (London: The British Museum Press, 2016).

Hunter, Michael, ed., Printed Images in Early Modern Britain: Essays in Interpretation (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010).

Werner, Sarah, Studying Early Printed Books, 1450–1800: A Practical Guide (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2019).